The Parable of the Good Samaritan acts out Jesus’ two simple teachings, “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” And “Love your neighbor as yourself.” It proposes an interesting hypothetical. What if you lived in a world set up according to the principles you espouse, how would you fare?

The parable is set up by a lawyer who wants to test Jesus. Keep in mind a lawyer is simply a teacher of the law. But much like lawyers today – it must be a universal phenomenon about law as such (the Sophists were the Greek version of the phenomenon) – he sees the law as an arena for parlor tricks, how to advance ones position while keeping the letter of the rules. Lawyers live in a world of “What does ‘is’ mean?” and “What’s the penumbra of a right?”

So the lawyer comes up to Jesus and asks what he must do to inherit eternal life. Jesus turns the question back on him, asking him how he reads the law. The lawyer answers with, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” Jesus says he answered correctly. If he does this, he will live.

The man then wants to justify himself. We’ve learned that the one who goes home justified is not the one who points out all the great things he’s done by God’s grace, but the one who begs, “Lord, have mercy on me, a sinner!” The proper response to “Love your neighbor as yourself” is to die to yesterday’s sinful self and rise to a new self, forgiven and ready to love neighbors.

But not the lawyer. “Who’s my neighbor?” Ah yes, now the lawyer in him comes out. What does “is” mean? This has always been the weakness of the law. Laws are wonderful, but the words making up the law change in their meaning, often on purpose by those who would corrupt its meaning. “Marriage is between a man and a woman.” Well, let’s just redefine what “man” is and what “woman” is. Or, what if three people identify as “man”? Or, we’ll change what marriage itself means. On and on we can go with this, which pretty much describes leftism.

Jesus doesn’t bite. He turns the tables on the lawyer with the parable he tells. “Who’s my neighbor?” asks the lawyer. What he really means is, “So, if I have to love my neighbor, then what are the limits of this rule? What is the minimum I have to do to follow this? And does that include non-Jews?”

So Jesus sets up another universe for the lawyer, painting him a picture for him to explore his ideas. What if the lawyer were in a world ruled by his way of thinking? Let’s say a man got seriously injured. He’s lying half-dead on the side of the road. That phrase “half-dead” is extremely important for our setup – it’s essential for the punch line. Because according to Jewish law – precisely the law the lawyer lived by – if you had contact with a dead body, you were unclean.

That explains why the first two men in the parable, the priest and the Levite, passed by on the other side. They didn’t want to become unclean. In that sense, they were being faithful to the law. They were being good lawyers. But they were leaving the man seriously injured.

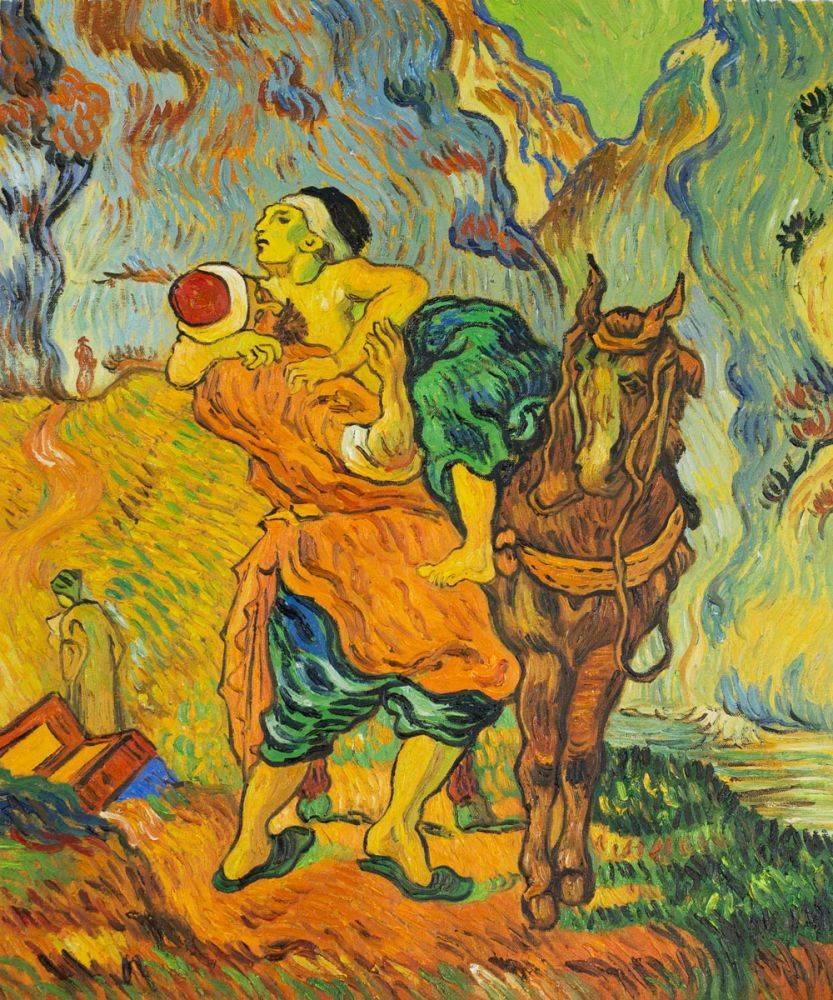

It’s not until an unclean Samaritan comes does the man get healed and well taken care of. The Samaritan is willing to risk becoming unclean in order to help the man.

Now, notice Jesus’ question to the lawyer. “So which of these three do you think was neighbor to him who fell among the thieves?” With this question, Jesus places the lawyer in the parable. The lawyer asks, “Who is my neighbor?” Jesus gives a series of characters and asks back, “Who was the neighbor to the injured one?” The lawyer is the injured man! Jesus proposes a hypothetical, how would you fare in the world you create by your understanding of the law? And the lawyer finds out who his neighbor is. It’s not the law people. It’s the one who had mercy.

It’s not about justifying yourself through fulfillment of the law. It’s about being dealt with mercifully, and doing likewise to others. What does that do to the law. Does that nullify it? Not at all. There is a way in the law to have contact with dead bodies and still come out clean at the end.

Here’s the law: “whoever touches anything made unclean by a corpse, …the person who has touched any such thing shall be unclean until evening, and shall not eat the holy offerings unless he washes his body with water.”

So, Jesus sets up a new way of being, a new universe clashing with the old one. It’s a world where people are willing to become unclean in pursuit of the well being of others, who are washed with water before eating the gifts of the altar. If we accept the premise that the cross was Jesus’ baptism, or rather the fulfillment of His Jordan baptism, then we see that Christ was the one who became unclean so that He might heal us.

We, after all, are half dead. Alive, but under a curse of death: “dead in trespasses and sins,” as St. Paul writes. And Jesus became our curse, for cursed is anything that hangs on a tree, so that we might become clean.

Being merciful is what the Lord wants us to do. That’s how the law is properly fulfilled, not looking at it as, “What can I get away with?” But rather, “In what ways does my neighbor need my mercy?”

A final point needs to be made about the neighbor. The parable is all about proximity. The Latin word for “neighbor,” after all, is the basis of our word vicinity. Who’s near by? Second, that proximity is bodily. It was because the man’s body looked half dead that the Levite and priest distanced their proximity from the body. “Neighbor” is something that only makes sense in bodies.

Let’s riff on this a bit as far as Gnosticism goes. Because Gnosticism sees flesh and materiality as deceptive, corrupt, and evil, it cannot teach “love your neighbor.” What is neighbor, but a cosmic mistake? Neighbor is nothing more than some two-dimensional symbol comprised of projections from your inner psycho-drama. Dad represents the patriarchy. The police officer is “the man.” A guy in a suit represents evil capitalism. Or, a youthful person of color living an alternative lifestyle represents being woke. Who these people actually are be damned. Neighbor be damned. Rather, everything gets abstracted and understood in cosmic terms.

Jesus directs us to the neighbor, to the one in our proximity. He doesn’t direct us to “humanity,” but to humans near us. And love of neighbor has nothing to do with well-intentioned programs to change the structures and systems you think will benefit “humanity.” No, Jesus directs us to that guy hurt right over there. Do that, says Jesus, and you will live.

Because that’s what Jesus does with us. In a sense, Jesus did nothing for “humanity.” The world goes on as fallen as it did prior to His coming. But Jesus does everything for His neighbors, for the ones proximate to Him. As St. James writes, “Draw near to God and He will draw near to you.”