Now as He drew near, He saw the city and wept over it, saying, “If you had known, even you, especially in this your day, the things that make for your peace!”

Think of the Jerusalem over which Jesus wept. It was a large city. There were all sorts of people. Most of them were probably relatively good people. They loved their children. They worked hard. They paid their taxes. They were religious, went to temple to pray, and offered their sacrifices. As St. Paul says about Israel, “I bear them witness that they have a zeal for God..”

But then he adds, “but not according to knowledge.” And it’s that lack of knowledge which Jesus alludes to when He says, “If you had known.” They lacked knowledge; it was hidden from them. That was the difference between their judgment by God through the Romans and their salvation.

This rubs us raw. How can it be that a simple bit of information can make such a huge difference in one’s final judgment? Shouldn’t we be more broad-minded? Shouldn’t we be thinking of ways to let all the good people in to God’s good graces? How many good people are out there, loving their children, working hard, paying their taxes, and worshiping their God zealously, even if ignorantly? How could we look at such people and not be happily hopeful for their good ending?

Jesus doesn’t. He doesn’t at all. He weeps. His heart is broken. He has insider information on the future, and He realizes their future has nothing to do with how good the people were, how they loved their children, worked hard, paid their taxes, and worshiped their God. Their future had to do with their embrace of a particular bit of knowledge.

And lest we be tempted to see “gnosis” in that word “knowledge,” remember that Gnostic knowledge (gnosis) is a beyond-the-mind knowledge, a knowledge of the heart, like an intuition, something “smelled in the air.” It’s beyond words, rationality, and argumentation. Words, rationality, and argumentation are things arising in a substantial world order, rooted in the elemental words which have a one to one correspondence to the substantial elements and actions of creation.

It has nothing to do with knowledge as the Bible teaches it. Knowledge as the Bible teaches it is based on the names first the Lord and then Adam gave to the world order; these are the elemental words arising from the substances and actions of creation. As the Lord directed cosmic history to its fulfillment in Christ and His cross, the words themselves play a primary role in effecting His will, just as they did on each day of creation.

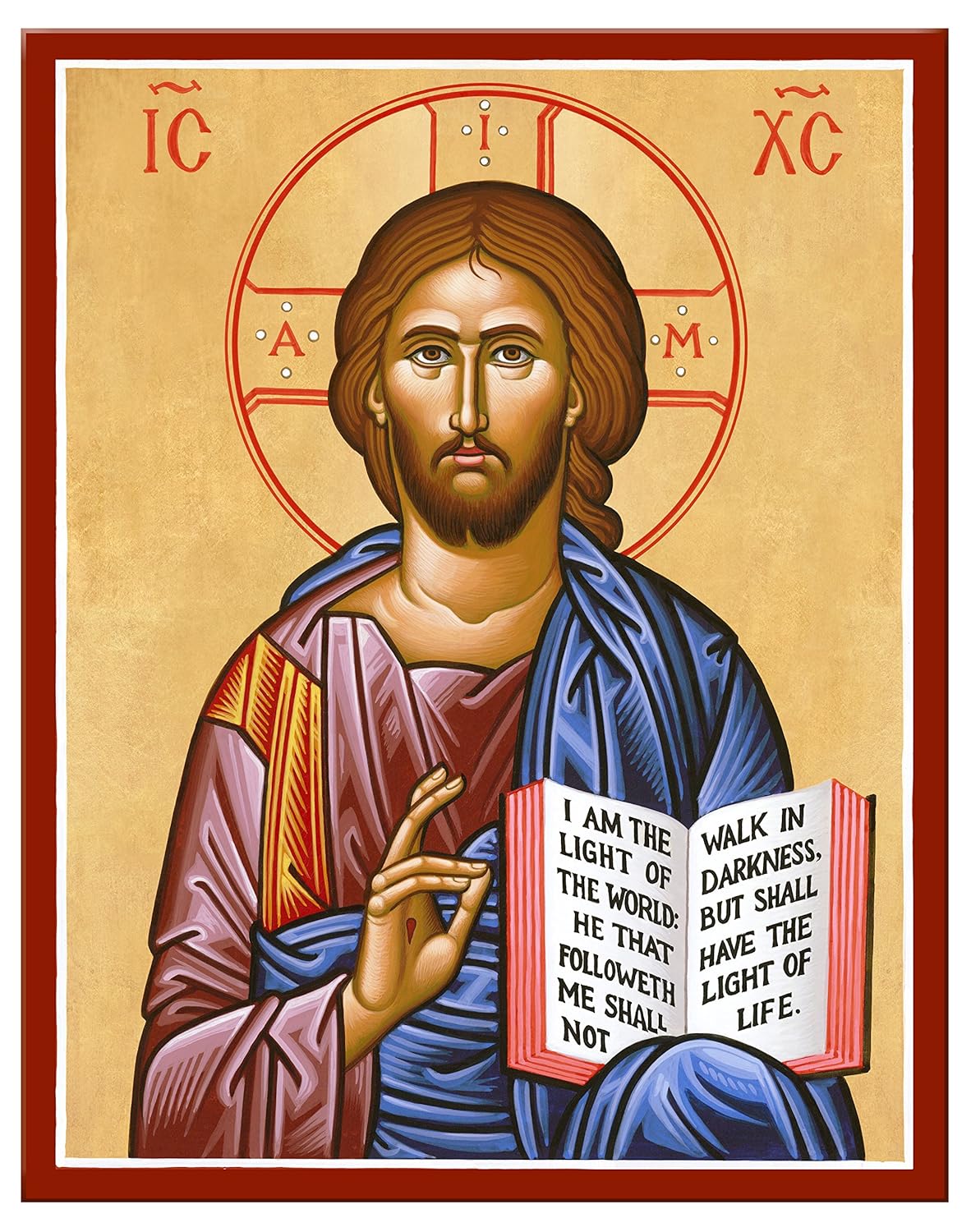

Words lead to knowledge. The Word leads to the ultimate knowledge. To know Christ is to know the truth. Christ is God in flesh. Truth is incarnate. Knowledge resides in the flesh and blood of Jesus.

So, for Jesus to say, “If you had known, even you, especially in this your day, the things that make for your peace!”, is no different than to say, “I am located in time and place for you here, in flesh and blood. If only you had known Me.”

And again, it didn’t matter how good they were. Why do I keep mentioning this? Because it’s so easy for us to see Christianity in moralistic terms. I don’t mean in the traditional Catholic/Protestant dichotomy of faith vs. works. I mean in a more macro, or perhaps psychological sense.

Perhaps due to the influence of revivalism, we tend to think of the Christian faith as the solution for sinners caught in some moral failure. They drink; they steal; they kill; they fornicate; they love money. They find Jesus, are forgiven, and now they’re changed people. They don’t drink, steal, kill, fornicate, and love money any more.

Here’s an interesting question. Is the Gospel a scheme to get us up to the standards of the Law? Or is the Law something to get us to the Gospel point? St. Paul answers the latter. The promise was put into effect way before the Law. The Law is our pedagogue to get us to the Gospel. Yet, especially in lieu of the Reformation, it’s tempting to see the story unfold like this. God created a perfect order, governed by the Law. Man failed. Jesus fulfilled the Law and caused man, in Him, to live up to the perfect standard governed by the Law. Jesus, thus, becomes the contingency plan. The Law is primary. In fact, had man not sinned, there would be no need for Jesus. And isn’t that they way things should have been? No need for Jesus?

Do you see the potential folly of this way of thinking?

But Jesus is primary. Jesus is the heart and center of creation, the goal of it. The Gospel is primary; the Law was put into effect as part of the unfolding of God’s mystery, to lead us to the Gospel.

So back to those good people of Jerusalem. It was not their moral failings that should have led them to Jesus, but their knowledge. They had no moral failings. These were the ones Jesus would have called “the righteous who need no repentance” who could have just as much been part of the great party (the older son; the 99 left behind; etc.) as the lost ones brought back.

Think again of St. Paul. His is the prototypical “come to Jesus” story, yet what a far cry is his story from the typical modern “come to Jesus” story. St. Paul was a good person. He was one of those residents of Jerusalem over which Jesus wept. He was zealous for God, so zealous He killed Christians. But in his context that would be something like an zealous CIA agent going after terrorists – the Christians made a similar impression in the minds of the religious leaders of Paul’s day.

St. Paul didn’t have a “I have sinned” moment like Jimmy Swaggert. He had a moment of gained knowledge that changed everything for him.

Now, when we speak of sin correctly, we can use the word in this context. Sin primarily (though not necessarily predominantly) in the New Testament means “to stumble in faith; to fall away in faith.” St. Paul sinned not because he, say, loved the bottle a bit too much; he sinned because he did not properly receive the true righteousness of God in Christ but attempted to establish his own righteousness.

Jesus wept over Jerusalem not because He saw a bunch of corrupt moral failures who wouldn’t come to Him for forgiveness. He wept over Jerusalem because the truth of who He was, their Savior, who yes did die for their sins, was hidden from them.

Now, why all this emphasis?

Because when we begin with a premise that the Gospel is the answer for moral failure, or that the Gospel is a scheme for personal self-improvement, we open ourselves on one hand to the accusation that we’re all a bunch of hypocrites, because look, we set up perfect morality as the premise of our faith, but look how far we fall short. On the other hand, lots of other programs of self improvement seem to work just fine, so why go to a church with a bunch of hypocrites when I can do quite fine with my regiment of yoga, wellness, and mindfulness.

And our attempts to “show them the mirror of the Law” and “show them how far short they fall” just comes across as arcane background noise. “I’m good enough,” they’ll say. To which of course we’ll say, “But God demands perfection or you go to hell! That’s why you need Jesus.” To which they’ll say, “Whatever,” and go on with their yoga.

We’ve been doing evangelism like this for years, and it’s backfired. That’s because we’ve become evangelists for the Law! “Here’s the Law; look how far you fall short; now here’s Jesus to fill in your blanks where you fall short.” That’s certainly not how St. Peter preached the first Christian sermon. His sermon went something like this, “The Old Testament prophecies of the day of the Lord are at hand; Jesus fulfilled it; He rules and is coming back to judge the world. Repent and be baptized every one of you.”

In other words, St. Peter gave them the missing knowledge Jesus said was hidden from them. The “repent” of his message wasn’t in the sense of “turn from your moral failings and get the forgiveness that Jesus gives,” but rather, “turn from your ignorant way of thinking and get with Jesus, who forgives all your sins and is your Savior.”

The Gospel is not a message of “how to deal with your moral failings,” but a message of “This is the cosmic truth of the universe that saves you from judgment.” Jesus’ wept over Jerusalem not because there were bad people there, but ignorant people. The solution wasn’t to browbeat the bad people into changing their bad behavior into good, but revealing to the ignorant people what the truth is. The bad behavior turning good happens as a fruit of the Gospel, but is not the core message of the Gospel.