More Luke. We get lots of Luke in the ordinary time after Trinity. We get lots of Luke in the historic lectionary. This being the last we see of Luke until the beginning of the church year, let’s do some statistical review on the historic lectionary.

Luke has more Gospels in the historic lectionary than any other Gospels, at 37.1%. Matthew comes in second (31.4%), with John in third (25.7%), and Mark at 5.7%. A few comments.

Several years ago when I began using the historic lectionary, I detected a more devotional, less academic tone in the entire year.

The three year lectionary’s focus on a single Gospel encourages an academic approach rooted in the view that Gospels need to be seen as a comprehensive whole, that this was how they were written and how they should be received.

I believe this subtly takes away from the divinity of the Word, from its cradling in the Church, a cradling I see as integral to the Scripture’s divinity. That is, the canon was self-authenticating not in a vacuum, but in and through its reception and placement in the Church’s liturgical life. This is not to be confused with any notion that “The Church gave us the Scriptures,” for, the Holy Spirit truly gave us the Scriptures. But just as He used authors to write it, He used hearers to validate the authors’ divine inspiration – sheep follow the Shepherd’s voice and not another.

The historic lectionary developed from the cradle of the Church as well, and therefore had a rooting in the pastoral and devotional life of the Church. The historic lectionary came from academics guided by newer understandings literary works, understandings which assumed the Gospels were first received as comprehensive wholes and intended to be received by their writers as such.

But is this how the Holy Spirit intended them to be received? And given the correlations between especially the first three Gospels but even all four Gospels, was this even how the writers intended them to be received? Early on, perhaps even as early as the writing of Revelation (with its four beasts around the throne), the four Gospels came to be seen as four integrated reflections of the one truth.

Perhaps to provide some light, we might look at the relation between early icons and later religious works of art. Early art, and icons, were not singed by the artist. They weren’t seen as we see art after what has been dubbed “the rise of the Self” in the 13th century, that is, as items of self-expression, to be signed. Rather, they were seen as craft work, as testaments to objective truths. The place of Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John’s personalities relative to the objective Gospel to which they testified is similar to that of John the Baptist to Jesus: “He must increase and I must decrease.” Or, as Jesus taught of the Holy Spirit: “He will testify of Me.”

This modern obsession with the writers’ personal feelings and perspective is an indulgence to the centrality of the Self in western cultural history and unseemly not only on biblical grounds, but even on academic grounds. Do we, for instance… Let me begin that thought again. Did we, for instance, once care (before they got politicized) about who wrote a grade school history text? No. The writers were reflecting important truths about history that we all agreed by consensus were important. So also the Scriptures.

That being said, the Lord did use human writers, and because we’re not Gnostics believing any human element is of essence defective, we do detect certain emphases in each Gospel. All the more reason why the historic lectionary verges on brilliance, insofar as it weaves together in a glorious comprehensive whole all four Gospels, rather than falling into the ruts of one evangelist’s emphases.

So, back where we began, after that detour into the merits of the historic lectionary. Several years ago when I first began using the historic lectionary, I detected a more devotional tone. I believe this is due to the prevalence of Luke in the season of Trinity – half of all Gospels in the Trinity season are from Luke. Luke has an emphasis on the Lord’s mercy that comes through the Gospels of ordinary time after Trinity.

A few quick comments on the rest of the church year. In very wide strokes, Luke also dominates the Advent and Christmas seasons (57.1%), Matthew owns the ordinary Sundays after Epiphany (57.1%), John owns Lent and Easter (54.5%), and Mark has precious few, but highly important, Gospels: Easter Sunday, Ascension Day, the feeding of the 4,000 (introducing inclusion of the Gentiles), and the only healing of a deaf man.

What does this tell us, given the emphases of each Gospel?

Matthew, with about a third of all Gospels in the historic lectionary, has the most consistent spread of Gospels in each season. This reflects his role as the first and foundational Gospel. When Jesus said disciples are made by “teaching them to observe all things which I have instituted” at the end of the Gospel of Matthew, a solid suggestion is to review those teachings through Matthew. The lectionary certainly does that. Matthew’s dominance in Epiphany ordinary time reflects his two chapter miracle marathon (Matthew 8-9), the revelation of Jesus’ divinity through His miracles being a big theme after Epiphany.

Mark’s all business. Bring him in for the big stuff: resurrection, ascension, unique healings. This fits his Gospel, which got down to business, like an evangelism pamphlet.

Luke dominates the more devotional seasons, Advent, Christmas, and the “green-for-growth” season after Trinity. Also, obviously, Luke’s material on the nativity of Jesus biases his contributions during Advent and Christmas.

John dominates Lent and Easter, particularly Easter. This reflects his “soaring” theology, like an eagle (his symbol). With Jesus’ teaching on His ascension, the Trinity, and the purpose of His crucifixion, it’s difficult to find better material to connect Holy Week with the Trinity season which follows seven weeks later. (Even the three-year lectionary acknowledges this, fitting John in throughout the three years, but particularly during the Easter season.)

Now, let’s turn to the Gospel for this week and make a few quick comments which will be expanded throughout this week.

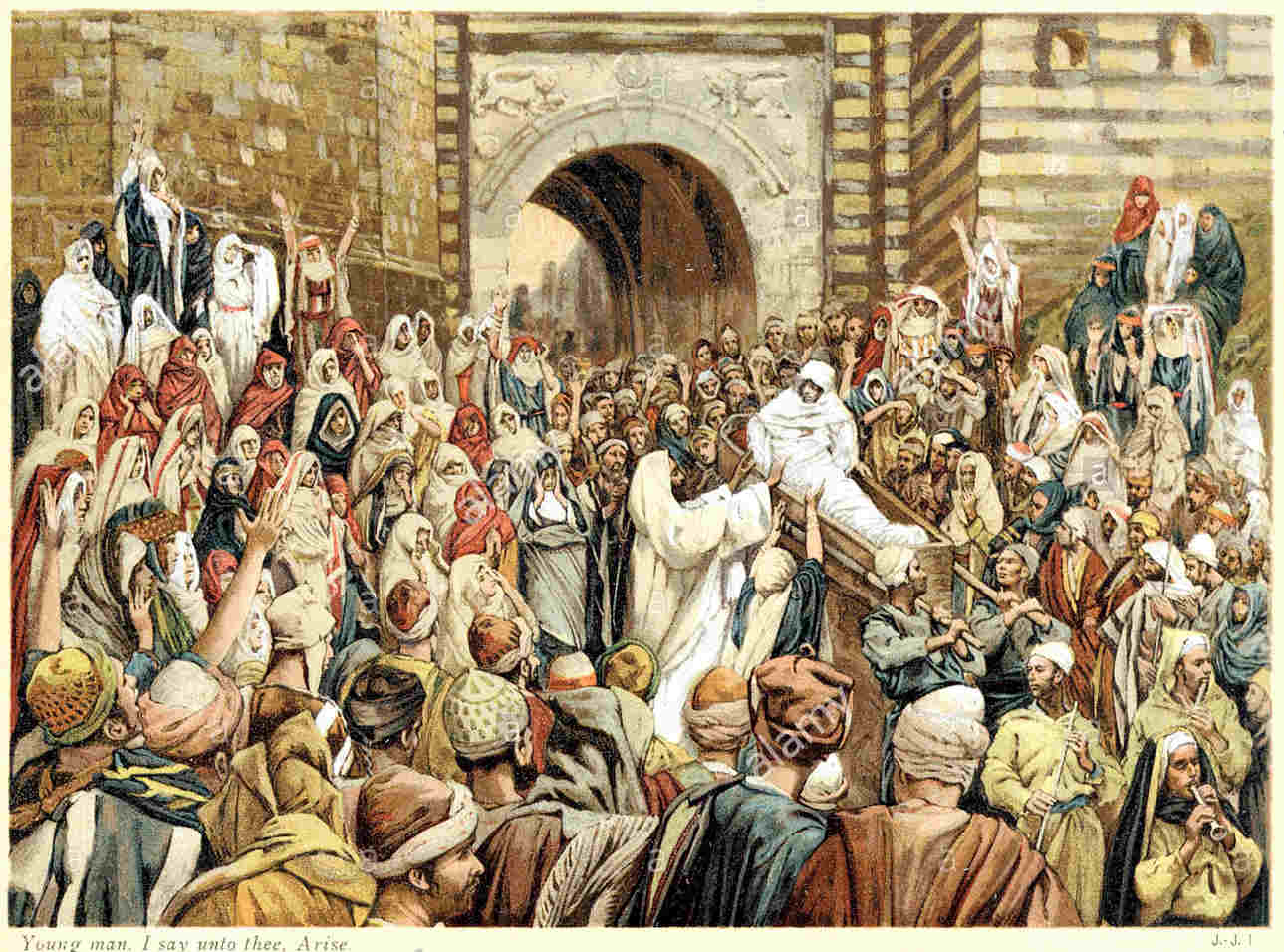

Again, if Luke’s contribution to the lectionary is indeed the pastoral, devotional tone, few Gospels better cap off his contributory Gospels. The commentators and hymn writers like to set up the Gospel as a confrontation between two crowds, a “large crowd” of death following the widow, and a “large crowd” of life following Jesus.

The two meet each other outside the city gates. Why? Because that’s where God’s Law places death – death has no place in God’s world.

When Jesus sees the woman, He has compassion on her. There’s the pastoral and devotional touch of Luke. He regularly testifies of Jesus’ mercy, not only as seen in His example, but also in what He teaches – God is about mercy; Jesus does mercy; Jesus wants His disciples to be merciful; this cannot be avoided in the Gospel of Luke.

Because of that great mercy and compassion, Jesus heals the boy, touching the coffin and in so doing becoming unclean. That unclean-ness would one day place Him where the Law had placed the boy by the Law, outside the city gates.

Jesus tells the boy to arise, and by doing so we see where our Lord locates our human identity, not in abstracted Selves disassociated from our physical bodies (so that one could say, “I’m trapped in my body”), but in our physical bodies. We’ll return to this theme later.

Finally, in response to Jesus’ great healing, we get another testimony of Jesus’ divinity in the Gospel of Luke. Luke’s Gospel, we’ve observed before, is least strong in laying down Jesus’ divinity in its opening chapters. Matthew reveals the name “Immanuel,” which means “God with us.” Mark begins with John the Baptist saying, “Prepare the way of the Lord,” and then preparing the way for Jesus. John has the strong “the Word was God…and the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” Luke has no such statements, but throughout His Gospel, He certainly reveals Jesus’ divinity, in ways like we see here. The people say, in response to Jesus’ acts of mercy, “God has visited His people.”

And that is exactly as Luke would have it. Jesus’ divinity isn’t so much a systematic teaching, or a title, or an ontological truth, but something realized in us as a consequence of His mercy: God is present among us in His mercy, to save us from death.