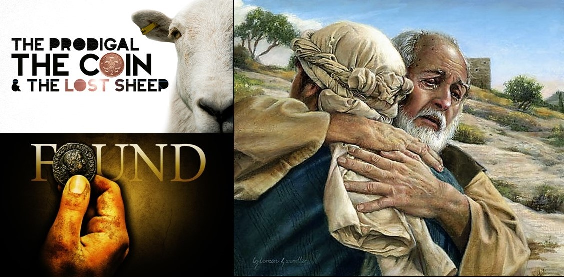

This week’s Gospel for the historic lectionary has two options. The first is what we’ll be meditating on for the most part, the parables of the lost sheep and lost coin. The second is the Gospel that follows these two parables, the parable of the prodigal (or lost) son.

Each of these parables has several things in common, with some notable differences. First the similarities.

Each parable begins with a “situation normal.” There are a 100 sheep altogether, or 10 coins, or 2 sons and a dad, all in perfect fellowship. These each belong to, in order, a man, a woman, and a father. Then, one of them becomes lost. How they get lost is where the interesting differences come in, but as far as similarities go, all of them become lost. Next, that which was lost becomes found. Here, the parable of the prodigal son has some interesting commentary on how the lost became found, one of the differences we can explore. Finally, upon that which was lost becoming found, the one who had lost said items, animals, and children has a celebration and feast to rejoice.

Now the differences.

The first difference is in the numbering of the items lost: 1/100, 1/10, and then 1/2. One wonders if each parable is intended to steadily stretch our acceptance of what is credible. A shepherd losing a sheep going out to find it, this we can imagine as reasonable. It’s his job to keep the flock and not lose any. One can even possibly imagine him having a party to celebrate, if, for instance, he was charged with another man’s flock.

A woman scouring her house for one lost silver coin, a drachma, which is worth about $50. Was that worth it? Maybe. Is it worth having a party over? That’s stretching it a bit.

A man having a party for a son who wished him dead, squandered a third of his property, lived with prostitutes, and partied until he ran out of his money, that seems downright absurd. Be glad he’s alive, sure, but a party? In a culture that so cherished the honoring of parents, any story that didn’t end with that son being disowned or even stoned is absurd. Isn’t this how Hollywood would end the movie, with some sort of comeuppance for the son?

Next difference. This one concerns how the lost became lost. With the sheep, there’s some active participation in the sheep to get lost. Yet, it’s a sheep! That’s what sheep do. With the coin, there can be no active participation. Coins get lost. That’s what’s done to them.

With the son, however, we have a bit more. We have a whole story how he gets lost. There is guile, greed, incredible self absorption, love of pleasure, and lack of humanity. And it’s all seemingly willful, unlike the coin and to a certain extent the sheep.

Or is it? And is this why the father behaves as he does? In other words, could we say of the son what we said of the coin and sheep, that “this is what they do.” In the bigger picture, is this what sinners do? We aren’t sinners because we sin; we sin because we’re sinners. That’s what we learn in catechism class. Is Jesus making a point about the son by setting up the sheep and the coin?

Notice the language the father uses. “He was lost.” That is, like the sheep and coin, something passively fallen into due to the nature of the thing lost.

Next we get to how the items, animals, and children were found. In the first two instances, that of the sheep and coin, the one who lost them goes to all extremes to find what was lost. He or she is the actor; the lost thing is completely passive. Not so in the parable of the prodigal son. There seems to be action on both the father and the son, with a heavy emphasis on the actions of the son to “be found.” He’s the one, after all, who “comes to himself.” He’s the one who goes home. He’s the one who makes movement toward the father. True, the father finally runs toward the son and restores him, but the son came all the way from a far country back home.

But, using the first two parables as context for the lost son, we’d have to say that the son remained in his state of lostness up until the father ran out to embrace him. He had, after all, already disowned himself from the family. He lost his inheritance. He was in every sense of the way lost from his status, perhaps even moreso than when he was eating husks. At least then he still held to the status of son. But when he returned home, he went as a servant, as one fully excluded from the fellowship. Truly, his being found only happened once the father embraced him and put a ring on his finger, and had the feast for him.

Now let’s get to interpretation.

The thing that perhaps pops out more than anything is how little psychological profile there is of the nature of repentance. Sheep get lost because that’s what they do. Coins are as passive as can be imagined. The son is the closest thing we get to a psychological spin, with the phrase, “he came to himself,” but even this does not make him “found.” It just sets him up for some misguided thinking.

No, in all cases the focus is on the one who finds what was lost, the shepherd, the woman, and the father. Why were the sinners and tax collectors coming to hear Jesus? Based on Jesus’ parables, we’d have to answer this question in as passive a way as we can imagine. Sinners and tax collects sin and cheat; that’s what they do. And when Jesus comes, they get found. That’s also what they do. So, they draw near to hear him. It’s what sinners do. Sinners naturally flock to Jesus. Because, to be a sinner is to be lost, and Jesus is the finder.

Like the prodigal son, however misguided he was, his first thought at “coming to himself” was to go back home. Similarly, the sheep surely, once lost, will naturally receive the shepherd when he comes. And the coin will do nothing but be found. Again, if their nature is to get lost, their nature just as well seems to be to accept being found.

Sinners draw near and hear Jesus. It’s what they do.

Of course, not everyone is a sinner, at least a sinner as defined by being lost and dead, as the parables define it. No, when sin is defined as personal defect that some willpower can fix, that takes us into different territory where we will not find the sheep, the coin, or the son. We’ll find a sinner quite confident in his ability to restore himself.

Or when sin is not defined at all, of course we won’t find sinners, and therefore none to draw near and hear Jesus.

But where there are sinners, you will find Jesus. Because that’s what He does. He’s the shepherd who seeks out the lost sheep. He’s the woman who scours the earth to find the lost coin. He’s the father making a fool of himself to restore the lost son.

Jesus and sinners somehow seem to find each other. Of course, Jesus’ first act in His ministry was to go where all the sinners were, in the Jordan, which tells us something about the sort of sinners He was looking for. Lost ones.