I am the good shepherd; and I know My sheep, and am known by My own.

The goodness of the Lord seems to be an important theme this week. On “Good Shepherd” Sunday we tend to focus on the wonderful, pastoral metaphor of Jesus as a Shepherd. But the qualifier that He’s the “good” Shepherd can sometimes be overlooked. Or, it gets glossed over quickly as, “Jesus is the good shepherd because He dies for the sheep,” the implication being, unlike other shepherds who raise the sheep to slaughter them

All too true. But there’s another context of the “good” shepherd, and there’s also a reason the Church chose to focus on the “goodness of the Lord” as it settled on an introit for this week’s Gospel. What’s that other context? It’s “I am the good shepherd; and I know My sheep, and am known by My own.”

The sheep know God not simply as shepherd, but as good. Hence the appropriateness of the introit corresponding to this Gospel: “The earth is full of the goodness of the LORD.

By the word of the LORD the heavens were made, And all the host of them by the breath | of His mouth.”

Incidentally, this is the exact theme brought up in the Venite (Psalm 95) sung at each Matins. Look at select words: “Oh come, let us sing to the LORD! …For the LORD is the great God, …In His hand are the deep places of the earth; …Oh come, let us worship and bow down; Let us kneel before the LORD our Maker. For He is our God, And we are the people of His pasture, And the sheep of His hand.”

The fact that the Venite is chanted daily in a service that goes far back in history, coupled with the fact that the earliest depiction of Christ in Christian art is as the good Shepherd, tells us something important about this theology: a central component of our faith is “knowing” God as a good God, the Good Shepherd, who holds all things in His hands. And keep this in mind in the context of the early church’s martyrdoms – they were the sheep led to the slaughter!

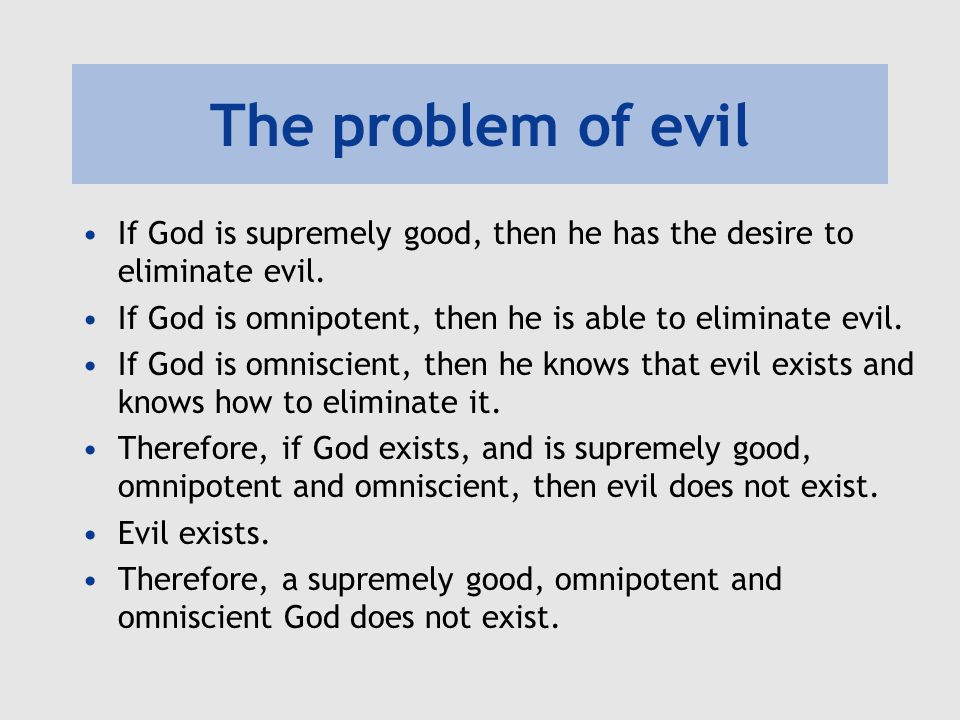

Indeed, that may not simply be a central component of faith, but the very structure of it! Let us consider the so-called “problem of evil” again. The problem only exists if evil exists. This is the problem for those who claim they gave up on God because they couldn’t fathom a world created by God with all the evils in it. The paradox they end up in is, now that they’ve gotten rid of God, they have no basis for saying anything is good or evil at all! If it’s all just survival of the fittest – T Rex chomping on some poor, hapless baby dinosaur – then evil might be relative to the baby dinosaur and its family, but in the big picture the action can be indifferent or even good (for T Rex).

The gnostic approach would be to single out evil as a “thing” with its own independent force – Satan, Yaldabaoth, the Demiurge – working against God and His aims. And then, the more practical gnostics will discern a good that is separate from the evil, and believe it their ordained mission to institute “good” in the world, usually through mass action, or politics. Or, as some of the evolutionary biologists put it, in their desperate attempt to re-establish Christian ethics in the moral vacuum they created, we have to transcend what our survival-of-the-fittest DNA has fated us to be, and so bring about good.

Because, good is what? Evolution establishes what used to be called sin and death. The strong survive over others until they don’t; that’s the rule. There is no “good” in that, because evolution prescribes nothing; it runs by an almost mathematical law. Is 2+2 good? The question is ridiculous.

So, what of the problem of evil? It’s not a problem of evil, it’s a problem of “I don’t have what I want. And what I want is not to be in pain from this alligator chomping on me because I accidentally wandered in a pond in Florida.” But the alligator is quite happy, as happy as we are eating our Big Macs!

And what of the Hitlers and sadists of the world who inflict unspeakable evils on the innocent? How much of that is a matter of sentiment and style as opposed to real evil, and by real I mean what ends up happening in reality. A young girl starves to death at Krakow after being beaten and forced to work in labor camps. King Herod kills the innocent with the sword. Heart-breaking. But in terms of real evil (and I’m still working things out according to the evolutionary world view), these are simply flourishes to the cold calculations of evolution’s march, flourishes unique to the human species – hey, T Rex has his flourishes and we have ours.

Ugly things happen every day. Right now an elderly woman lies starving in bed, dying, because her children are busy with their lives. The sentiment level is different, but the coldness of evolution’s calculations remains the same. The children are adding more net value to the improvement of the species by what they’re doing than by giving comfort to some random “animal” going off in the corner to die.

How many old squirrels are in the same situation as the woman, off in some lonely hole dying? How many young rabbits are in the same situation as the girl at Krakow, starving and at the mercy of some predator? Maybe the predator isn’t a jerk about it – again, humans add their own little flourishes unique to our species – but certainly ripping off the flesh from a live animal is kind of…jerky.

So, the only way we can lift these sad situations up to the level of evil is to have such a notion as evil in the first place. And the only way this can happen is to get out of the materialist cosmic order, which is to say, to introduce God into the equation.

The Gnostics introduce God as completely outside this material realm (which is, incidentally, one of the reasons why Gnosticism is so popular today, because science has declared the entire material realm off limits to God, so people are forced to hunt for him in transcendent realms, which is exactly as the Gnostics believed). Good, according to this, is in this transcendent realm; evil is what our material world has resulted in. Hence the problem of evil.

Christianity, and this week’s Gospel, introduces something completely, actually mind-blowingly different. Christianity looks at this world with all its evils and says, “The earth is full of the goodness of the Lord.” The sheep “know” the Lord as good. How can this be, accept by faith. Which is why, again, this is so structural for faith. It’s why St. Paul says we should give thanks at all times for everything in the name of Christ. By faith the Christian’s soul is full of God’s goodness in everything that happens, and he can’t help but be thankful at all times for everything…in the name of Christ.

This faith looks above and ahead, to where Christ is sitting and to when Christ will return, and knows He will rule in righteousness, our Good Shepherd making everything right. He’ll remove everything that causes sin and take tears away.

Again, with this faith the problem of evil melts away. What’s evil that God isn’t turning into good, something He demonstrated when the Shepherd became the slaughtered sheep, out of which eternal life flows?

It’s either that, or we look at the evils of the world and howl into the silence about it. Or does anyone know another way?