There are two liturgical elements that often befuddle non-“small c”-catholics. One is the crucifix, the other is the making of the sign of the holy cross. Like all other liturgical elements, these things are reduced to “man’s traditions” and “rituals” which have nothing to do with the true faith of the heart. Passages like this are cited: “These people honor me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me.”

Many churches remove all hints of the crucifix, or even the cross, and strip any and all symbology out of the church. The idea is such things smack of “churchiness,” which if you break down, comes back to the same supposed problem. Church, so the thinking goes, is not about externals, rituals, scripted speech (like the Lord’s Prayer, which, um, Jesus commanded), and any ordained thing or person.

Rather, the idea is, the true, “authentic” stuff is going on in the heart. And each person has a “personal relationship” with the Lord. Externals get in the way and substitute for a “real faith.” They in fact become idols, things people place more divinity in than the Lord Himself. And this is what the “second command” rejects. What is the second commandment? “Make no graven images.” (Now you see why the evangelical tradition adds this commandment to the traditional numbering and combines the ninth and tenth commandments.)

Even the idea of “ordained minister” has to give way to something new, something akin to a guru or shaman who behaves more like a motivational speaker – someone to coach or encourage you on your personal walk with the Lord. Anything but the idea that the minister is an ordained “go between” between you and God.

We’ll deal with this “go between” idea in a later meditation. That, after all, is exactly what Jesus ordained in this week’s Gospel. But let’s deal with this idea of externals – like the crucifix or the sign of the cross – and whether they are appropriate for faith.

As long as we have an “external God,” having external symbology can and should be part of the church. It certainly was in the Old Testament, and the writer of Hebrews talks about “the copy and shadow of the heavenly things, as Moses was divinely instructed when he was about to make the tabernacle. For He said, ‘See that you make all things according to the pattern shown you on the mountain.’”

The Old Testament temple was a “copy and shadow” of heavenly things. The temple was a physical manifestation of heavenly realities, something that was a consequence that the Lord certainly broke the barrier between transcendence and imminence with His people, appearing to them in “angelmorphic,” substantial forms, like the burning bush and other manifestations.

Now, the Hebrews writer has a “but” after this passage. He writes how Jesus is the fulfillment of the copy and shadow, so the copy and shadow have passed away. The prophecy of Jeremiah typifies what’s going on: “Behold, the days are coming, says the LORD, when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah – not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers …this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the LORD: I will put My law in their minds, and write it on their hearts…they all shall know Me, from the least of them to the greatest of them, says the LORD. For I will forgive their iniquity, and their sin I will remember no more.”

See? There it is! “Not according to” the religion of symbols, candles, incense, sacrifices, and written tablets – that’s the Old Testaement! Rather, “I will write it on their hearts.” Jesus and His Church represents a revolution from one mode of religiosity – of externals – to a new mode of religiosity – of the internal heart. That’s one of the main messages of the Gospel, and that’s also why Jesus was really against the Pharisees – they were stuck in their rules and rituals, their externals, and didn’t have an authentic, heart-felt faith.

The idea of revolutionary change in the mode of God’s being is actually one of the many Gnostic heresies, similar to that of Joachim of Fiore, whom we’ve discussed periodically. He believed in the revolutionary change of ages, from the Age of the Father to the Age of the Son, and then from the Age of thee Son to the Age of the Spirit. He divided up history into three ages, but today’s externality-rejecters divide history into two ages, the Age of the Old Testament God and the Age of the New Testament God. This latter breaking up of history is actually more true to original Gnosticism, which rejected the Old Testament God.

(And the biggest irony is those who hold to this in practice, often in theology are Old Testament atavists, wanting to re-introduce sabbatarian laws, hold to obscure Old Testament regulations, and make the heart of the Bible the land promise to Israel, as if Jesus didn’t already rebuilt the third temple!)

By huge contrast, Jesus did not come to revolutionarily change things, but to fulfill. And true, His new wine doesn’t fill old wine skins, which is precisely why the elements of the Old Testament fall away, the shadow replaced by the substance.

It’s the difference between seeing your wife on Facetime for a year (say, on a military deployment) – that’s the shadow of the substance – and then having her in the flesh. But that development doesn’t change the mode of her being. When she was a shadow, she was still flesh and blood, and in person she’s exactly the same.

The same is true with the Lord. He doesn’t change the mode of His being from the Old Testament to the New Testament. If in the Old Testament externals were essential to how He communicated Himself with His people, so also in the New Testament, even more so! As Christ is the culmination of “God as an external, corporeal manifestation.”

If anything, if you could talk about a change in God’s being, it was from non-corporeality to corporeality! In other words, if the Old Testament dwelled on the promises and shadows of God’s future corporeality, the New Testament has the substance, and therefore in the New Testament age, we should have even more a focus on externals!

This was how the Church ended up a the point of embracing icons and pictures in the Church. Back then, there were people who used the “second commandment” against graven images to reject any sort of symbology in the church. At that time they were heavily influenced by Islam, which doesn’t have any depictions of God based on that “commandment.”

Islam essentially had a Gnostic understanding of God, that he transcends names, words, and images. Some Christians embraced this theology and rejected images – how can an image communicate anything about God? The orthodox Church stood strong on the central truth of the Christian faith. God broke the barrier between transcendence and corporeal imminence when He took on flesh and dwelt among us. If God is here physically, why would we not be able to depict Him? Could you have taken a picture of God with a camera when Jesus was around? Of course you could have! Because Jesus is God!

So here’s a better way to understand what’s going on in Christ, from St. Paul: “So let no one judge you in food or in drink, or regarding a festival or a new moon or sabbaths, which are a shadow of things to come, but the substance is of Christ.”

This strikes against both the atavists who can’t give up Old Testament theology, and also lays down the basis for New Testament externals and symbology. The substance is Christ!

Christ’s body, His Church, is that substance as much as Jesus Himself is that substance. Substance means “real stuff,” even physical stuff. There’s your basis for externals.

Where there is substance there is also form. What form? What informs those forms? I would say a safe answer is “faith.” Faith in Christ, the flesh and blood substance Who Himself is communicated to us through the ordained, “forming” words of Scripture. And here the heart comes in, for “where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.”

And where is our treasure? In heaven. So St. Paul says, “If then you were raised with Christ, seek those things which are above, where Christ is, sitting at the right hand of God. Set your mind on things above, not on things on the earth.”

Yet, Christ is present in the Church, where two or three are gathered in His name. And He is there physically, else we are antichrists (for St. John defines the antichrist as one who denies that Christ “has come [and still is]” in the flesh). And we don’t want to be antichrist. Do we?

Jesus’ physical presence at the right hand of God in heaven runs the cosmic architecture of the physical time and space His body, the Church, fills up. Nothing in that time and space is arbitrary, and we see that the Lord’s obsession with detail in the building of the tabernacle and the externals of worship – how much of the Torah is devoted to it? – absolutely translates into the New Testament. How can it not, unless we deny that Jesus is physically present in the Church, or that the Church is truly His body, or that He’s still flesh and blood. But again, this is what antichrist believes, so we don’t want to be him.

On these terms, the church that deliberately (not because of lack of funds) makes a church look like an auditorium devoid of any sense of sacred space and time is actually confessing an absent Christ, or a Christ only present internally, non-corporeally. That’s the Antichrist Church.

Rather, a Church would be careful that its cosmic architecture – the elements manifested in space and time – reflect hearts anchored in the one sitting in heaven who also happens to be present physically in and through His body, the Church.

OK, is that enough set up for the punch line?

“And I will pour on the house of David and on the inhabitants of Jerusalem the Spirit of grace and supplication; then they will look on Me whom they pierced.”

Our hearts are ever looking upon the one whom we have pierced. This is because we are in the post-Pentecostal time after which the Spirit of grace and supplication has been poured out. To look is to use one’s eyes. Eyes are physical things that witness things. How cannot the crucifix arise from this reality? The crucifix of course is a symbol, but so much more than a symbol, representing in physicality what our hearts are centered in. It’s not worship to reverence the crucifix. Nor is it an idol.

An idol is a projection of the Self’s desires. Projecting on a screen some poetic or culturally “relevant” idea of Christ the pastor dredged up while he thought God was talking to him through the inner whispers of his Self, that’s an idol. Setting up in physical form a central truth of our faith – that we present Christ crucified, that we look on Him whom we have pierced – is hardly an idol, but rather a reminder that the heart of the Gospel is centered in exactly what Jesus did when He presented Himself to the disciples as the pierced one: giving out the Spirit of absolution and ordaining the authority of the Church to forgive sins.

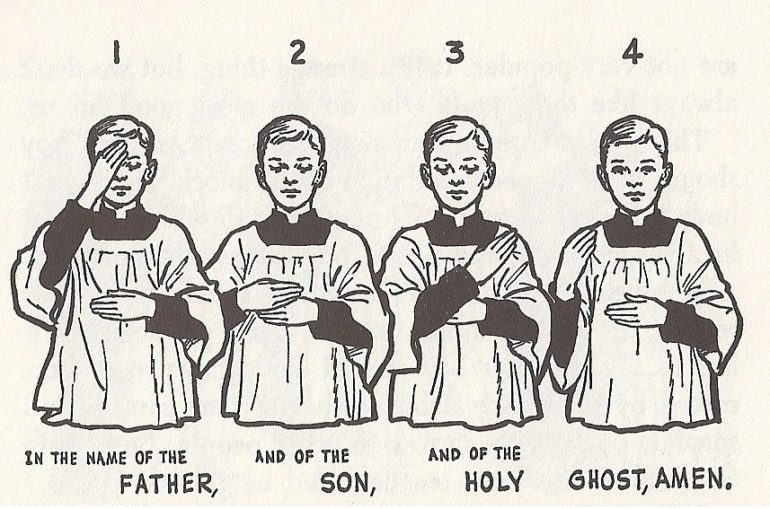

It’s no coincidence that churches without the crucifix are often devoid of the teaching of the cross, devoid of giving forgiveness (moving on to bigger and better things), and very often devoid of that other gift of the crucifix, the name of our Lord. And this leads to making the sign of the cross “in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.”

That of course is the baptismal name, so making the sign of the cross is a reminder of our baptism. But why the action of making the sign? And why is that sign connected to the name? Well, on purely theological grounds, there’s an easy answer to that question. We are baptized into Christ’s death even as we’re baptized in His name. Name and cross go together. Again, what faith anchors in manifests in physical signs.

But there’s a biblical basis as well. The sign of the cross goes way back, and even precedes the New Testament. At a point of pending judgment, God had told the prophet Ezekiel, “Go through the midst of the city, through the midst of Jerusalem, and put a mark on the foreheads of the men who sigh and cry over all the abominations that are done within it.” This mark protected them from judgment.

Revelation draws from this (and here’s where the name comes in) when it talks about the 144,000 with the name of the Lord on their foreheads, and says later, “They shall see His face, and His name shall be on their foreheads.” This name on their foreheads spares them from pending judgment.

But what was that “mark” God told Ezekiel to put on their foreheads? It was the Hebrew letter Tau, which, before you get excited, doesn’t look at all like a “T.” Now you can actually get more excited, because in the cursive Hebrew current at the time – the sort of Hebrew Ezekiel would have been writing on their foreheads – the shape of the Tau is not only cruciform, but cruciform in a “one stroke” manner! Exactly like making the sign of the holy cross.

Very early on, making the sign of the holy cross on the forehead and on the breast of the candidate for baptism was part of the baptismal liturgy. It confesses in physical form what the Lord Himself had Ezekiel physically do, and which the New Testament most certainly continues in the baptismal theology.

If our faith is grounded in a physical – and physically present – Lord Jesus who is sitting at God’s right hand, then there are cosmic realities faith will express in the architecture, space, time, and actions going on where faith is lived out in the Church. Nothing is arbitrary. Everything is informed by this faith. How can it not be?