![]()

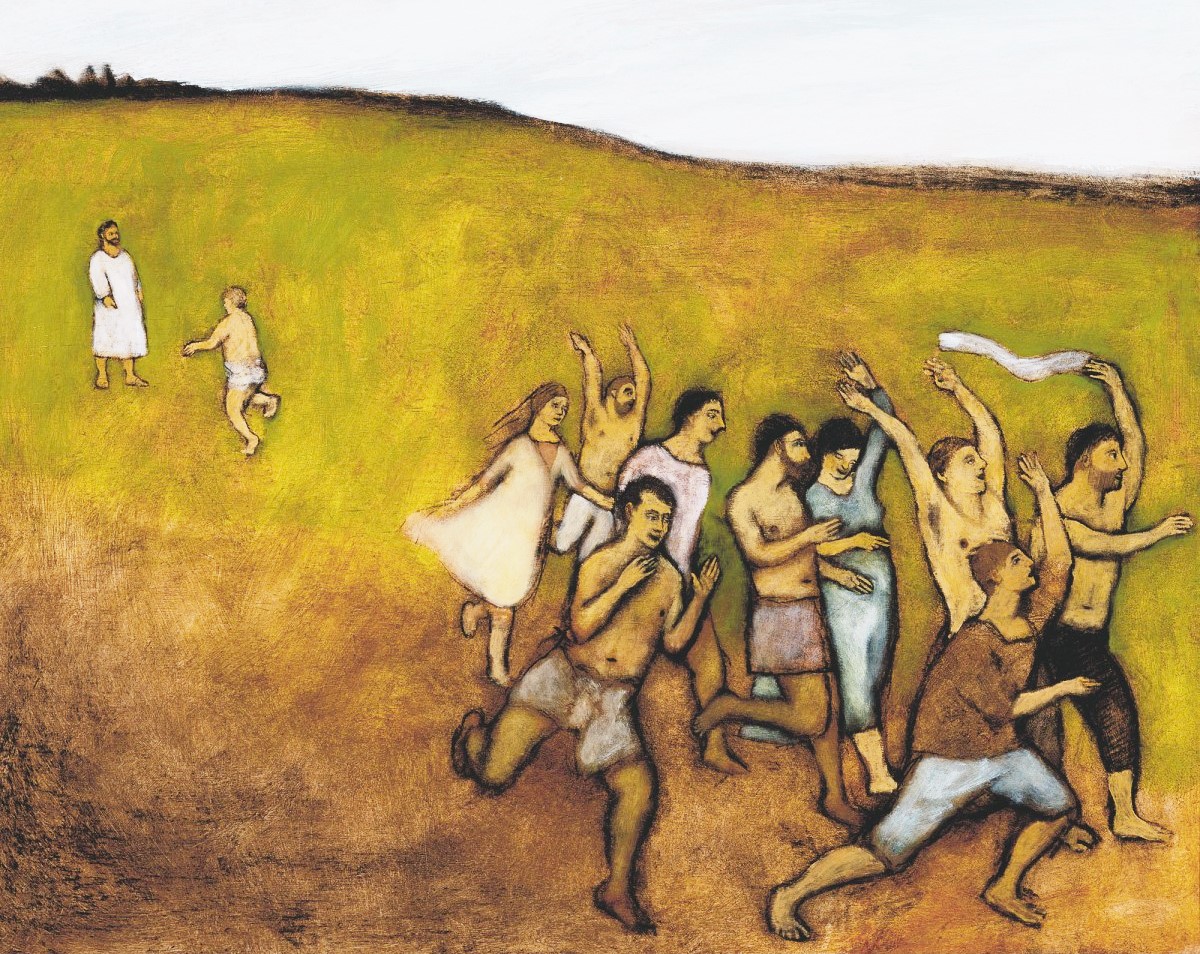

So when He saw them, He said to them, “Go, show yourselves to the priests.” And so it was that as they went, they were cleansed.

At this point in the Gospel, this passage, Jesus stands at the fork in the road as a road, acting both as a figure of the Old Testament and the New Testament. “Go, show yourselves to the priests.”

At face value that looks like something out of the world of the Old Testament. There is the uncleanness of leprosy, rituals for dealing with lepers, and protocols for being declared clean by the priests. Jesus, who was “born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law,” gave the right answer as far as the Law went. They came looking for healing; He in a sense winked at them and said, “You’re going to get your healing, because you came to me begging my mercy, so go on, get outta here and get your declaration of cleanness.”

In obedience to Him, they all departed. On the way they were healed. We assume they all rejoiced. Yet, nine of them, as they rejoiced, continued to obey Jesus’ words, “Go, show yourselves to the priests.” Meanwhile the one Samaritan returned to Jesus. Was he disobeying Jesus’ words? Jesus said “Go to the priests,” and this Samaritan goes to Jesus.

Here, Jesus becomes a New Testament figure, and we see, just as we did about two thirds of the way through the parable of the good Samaritan, a new world dawning, arising out of the Old Testament world. We see new wine skins prepared to serve the new wine of the new creation.

The question is, what does this mean? What does the new world look like?

The axiom we’re working with, of course, is that Jesus is the true priest, and whether the Samaritan knew it or not, he was truly being obedient to Jesus. Jesus said, “Go, show yourselves to the priests,” and he did. He showed himself to the priest that fulfilled all priests, whose ministry coalesced every Old Testament rule, regulation, and ritual and in turn, was carried on by new “priests,” the apostles.

We like that axiom, don’t we? But as with all things Jesus does with us in the Gospel, it’s never as simple as it first appears. Because Jesus uses the plural for “priests.” “Go see the priests,” He commanded, and the Samaritan goes to one person, not to all “the priests.” Aside from possible cultural issues like, did each leper go to one priest? Or, were several priests involved in the declaration of cleanness? (That’s not what the Old Testament Law said: “This shall be the law of the leper for the day of his cleansing: He shall be brought to the priest.”)

So what do we do with the plural?

Perhaps our axiom is wrong. In that case, we’d have some justification for saying Jesus endorses disobedience to Himself. Jesus commanded, “Go to the priests,” and the man disobeyed Jesus, and Jesus praises Him. What does this mean? Are there cases were we may disobey Jesus, when it comes to the Law at least, and He’ll praise us?

Maybe. Maybe faith covers a multitude of sins. Maybe being thankful for our healing and worshiping God in Christ Jesus trumps being obedient to Jesus. Because, after all, how much of Jesus’ teaching on the Law do we disobey? Who doesn’t get angry? Who doesn’t hate? Who doesn’t lust, get worried, and swear? Who doesn’t hate his enemies? Who doesn’t fall for Mammon’s temptations? Perhaps when we come to Jesus with our moral scars, and He says, “Here’s what the Law says,” and then forgives us, the proper response isn’t to go running still to the Law, but to go find Jesus and worship Him.

The pitfalls of this interpretation are its antinomianism, as well as the confusion of distinctions of laws. Going to the priest was a ceremonial law. Jesus consistently lessened the hardship of these laws: the disciples eating grain on the Sabbath, healing on the Sabbath, the Samaritan going near what looked like a corpse, Jesus’ teaching about what goes in the mouth not really mattering anymore. Meanwhile, Jesus’ moral teaching consistently upgraded the Law in more difficult ways: don’t get angry, don’t hate, don’t lust, love your enemies, and so on.

The antinomianism is the real danger, as if Jesus’ whole point was simply to free us from, and not fulfill, the Law. If we cannot discern how Jesus fulfilled every single Old Testament Law, we make Him into a liar, for He Himself said every jot and tittle of the Law will be fulfilled. So, when Jesus said, “Go to the priests,” at some point we have to believe, He absolutely meant it. Just as He completely endorsed the rules about corpses, eating grain on the Sabbath, and all other Sabbath Laws.

So our axiom should be able to remain. Jesus gave the lepers a command, one group obeyed in an “old wineskin” way, the Samaritan did in a “new wineskin” way. Jesus is the priest to whom He went.

But again, Jesus said, “Go to the priests.” Where were the other priests?

One solution is, perhaps Jesus fulfills all priests, as Hebrews puts it, “Also there were many priests, because they were prevented by death from continuing. But He, because He continues forever, has an unchangeable priesthood.”

This interpretation also has the benefit of getting Jesus back on track with Old Testament law, which required only one priest. But obviously the tone of the previous sentence is ridiculous. Jesus doesn’t get off track. No, there’s a reason for the plural. Consider, when Jesus healed the leper earlier in Luke’s Gospel, He didn’t use the plural. He said, “show yourself to the priest.”

Were there other priests with Jesus? Of course there were, His disciples. We hear from Revelation: “To Him who loved us and washed us from our sins in His own blood, and has made us kings and priests to His God and Father, to Him be glory and dominion forever and ever. Amen.”

“Go show yourself to the priests” would, in this case, mean something to the effect of, “Go to church.” That’s where New Testament priests gather and offer their sacrifices. That’s where the power of healing resides, where two or three are gathered in Christ’s name. That’s where the declaration of our cleansing happens, in the Church’s creed and worship, in the mutual consolation of the brethren occurring liturgically.

Is Jesus teaching a new priesthood here? It seems He is, else we’re stuck in that conundrum of the Samaritan not obeying Jesus. If this is the case, it sort of builds off last week’s Gospel of the good Samaritan, but in reverse. There, the old priesthood left a man half dead because they lost their way on the Law – the Samaritan risked becoming unclean for the sake of love, representing Jesus’ new priesthood in which He became unclean on the cross so that we might have life.

This week, a Samaritan, now the one needing healing, recognizes the true priest to Whom He should offer His thanks and worship. The old priesthood was good; but this one is so much greater.