“A voice was heard in Ramah, Lamentation, weeping, and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children, Refusing to be comforted, Because they are no more.”

The city Ramah was the staging area near Jerusalem where Israelites were mustered before being exiled in Babylon during the days of Jeremiah, the prophet Matthew quoted. The city was in the tribe of Benjamin, who was a son of Rachel, hence Rachel’s weeping.

Being “no more” really meant, “being no more in Israel,” since in fact, many remained alive; they were just exiled. A note on this. We moderns don’t understand how being disconnected from our homeland can mean being “no more,” or having a lost of identity. We mobile moderns will live here and there without too much lost of identity. Not so in the ancient world. One’s identity was wrapped up in family and place of residence. Think “Jesus of Nazareth,” a name first referenced in this week’s Gospel and the name which ended up on the cross. It was Jesus’ earthly last name. (“Jesus Christ” is more His Church name.) Matthew pinned Jesus’ identity to this name – “He shall be called a Nazarene.”

Modern dislocation from place and family name is among the several reasons for our modern neo-gnosticism, which sees any identity “imposed” from the outside, like place or family name, as “inauthentic” stuff we need to escape, rebel against, or transcend in order to be our true, authentic Selves. Well, if already our families are hodgepodges of different biological mommies and daddies, and moving from one location to another half way around the world is as easy as a half day plane ride, it certainly feeds the idea that “I” am something other than where or whom I’m from.

Not so the ancient Israelites. To be “no more” is to be exiled from your homeland. And that is what they became, “not a people.”

For this reason “Rachel” wept. Who is Rachel? Poetically it’s no different than, say, depicting Lady Liberty weeping when the country is the victim of a terrorist attack or school shooting. It’s something more than a woman crying over her lost children. It means so much more. There’s a sadness about the state of affairs: exile, a King Herod snuffing out all hope of a Messiah, the triumph of political powers.

Jesus wept too, putting a real flesh and blood face to the sort of weeping “Rachel” does. Jesus fulfills many Old Testament types. Jesus incarnates Rachel. He weeps over death and punishment, as He wept over Lazarus’ death and Jerusalem’s future destruction. It’s a weeping not just over events, but what those events represent in the grand scheme of things, things so sad God cries.

Jeremiah promised Rachel’s children would return to Israel. The homeless would have a home. Those who “were not” would regain a new identity. But the fulfillment of this prophecy was not as many thought. St. Peter writes of the true fulfillment: “But you are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, His own special people, that you may proclaim the praises of Him who called you out of darkness into His marvelous light; who once were not a people but are now the people of God, who had not obtained mercy but now have obtained mercy.”

What of the children in Bethlehem?

These were Rachel’s children, children of the promise. Their “no more” wasn’t about losing their homeland, but was quite literal. The sadness engendered was real, and represented something quite sad, the triumph of political powers against God’s plan. We should safely suspect that God cries with Rachel, in fact may be Rachel weeping. Why? Because the world would reject its Savior, and this was but the beginning of the rejection, the lengths the world would go through to attack its Savior.

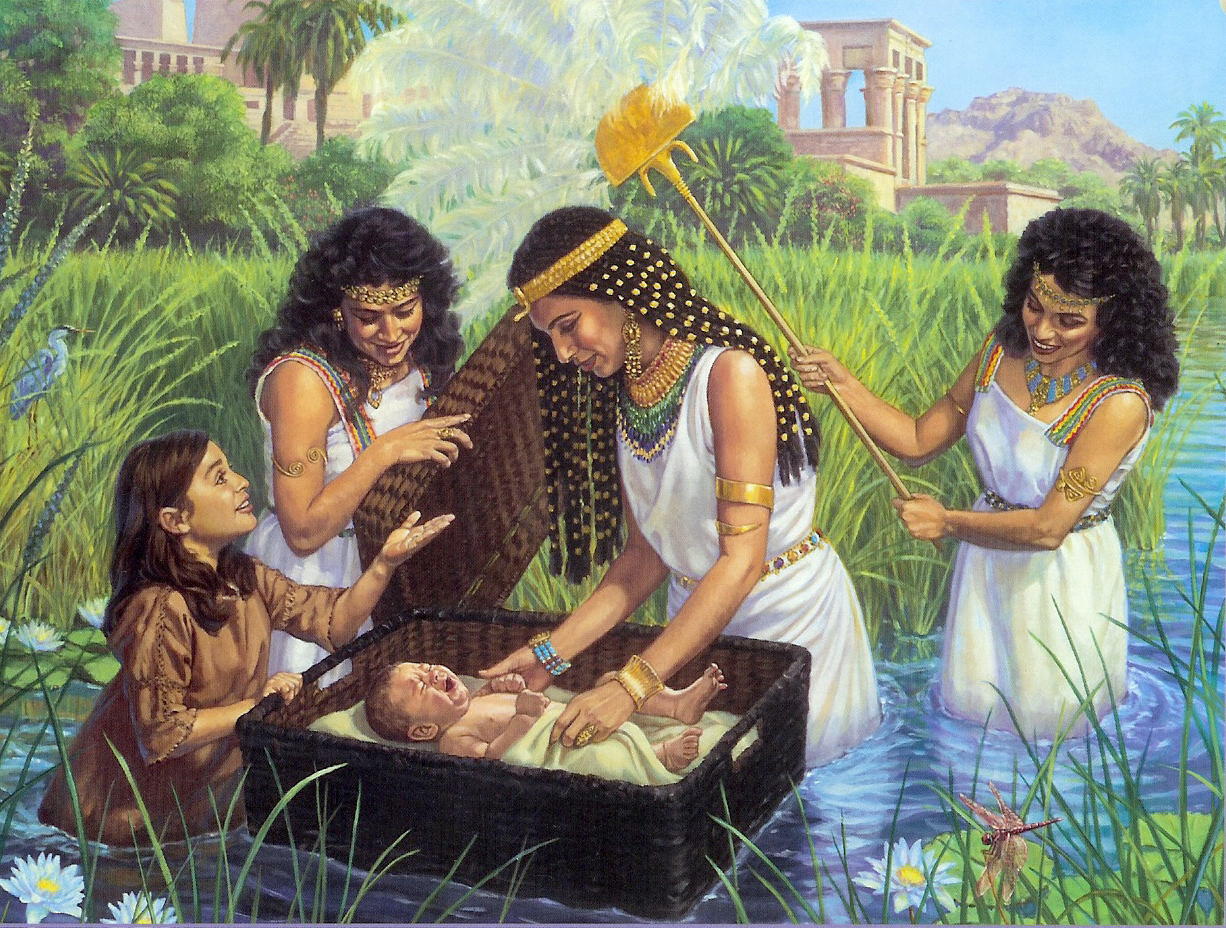

But the Lord always hears the cries of the martyred blood crying out from the soil. He’s been doing so since Abel. And the holy innocents were indeed martyrs. They were children of Rachel embraced in the promises given Abraham, to be as the stars in the sky, born from above, in a sense, baptized, or to use a concept from the early church to explain how un-baptized martyrs (or the thief on the cross) were saved outside of water baptism, baptized in blood.

The question of their faith is as ridiculous as the question of infant faith. Jesus is the one who sets the standard of faith: “[U]nless you are converted and become as little children, you will by no means enter the kingdom of heaven.” And “Let the little children [i.e. infants] come to Me, and do not forbid them; for of such is the kingdom of heaven.”

And evidently whatever faith infants have involves not only knowing the Word of God but professing praise: “[Jesus said,] Have you never read, ‘Out of the mouth of babes and nursing infants You have perfected praise’?” And then there’s St. Paul’s words to Timothy, “But you must continue in the things which you have learned and been assured of, knowing…that from infancy you have known the Holy Scriptures.”

Knowing the Holy Scriptures and praising God are within the capabilities of infants, and such activity is part of the faith they have, which is the standard of faith all people should seek. This forces us to de-adult-ize our typical understanding of faith – as something related to emotion, intellect, and will, and see it as something other than that. Jesus’ words force us to conform our understanding of faith to His word.

You don’t have to have the psychological faculties of intellect, will, or emotion at work to bleed for Jesus. Bleeding for Jesus, or dying, comes not from internal psychological faculties but is given from the outside. It’s not unlike the sacraments of baptism, the preaching of the Gospel, or Holy Communion, which also can create infant believers. The external, physical, material substances of these things causes a conformity to those to whom it is given, and this is the faith.

Similarly, the building of the ark created the external “thing” in which anyone so conformed would find salvation. A baby born on the ark, so long as his existence conforms to the external realities of the ark’s structure, will enjoy salvation from that ark. So also the sacraments, the Word of God…and martyrdom.

What sort of dying and suffering for Jesus do we do with as much unawareness the infants had, which could be called a “holy innocent” dying or suffering? What sort of dying and suffering does our Lord grant us, which qualifies us for the awesome reward, that He Himself cries for us? What sort of salvation is our Lord working for us when we are in a state of unawareness similar to the holy innocents?

It is such questions the murder of the innocents raises, once we can get beyond the modern evangelical understanding of faith, as something only possible for the psychologically invested.