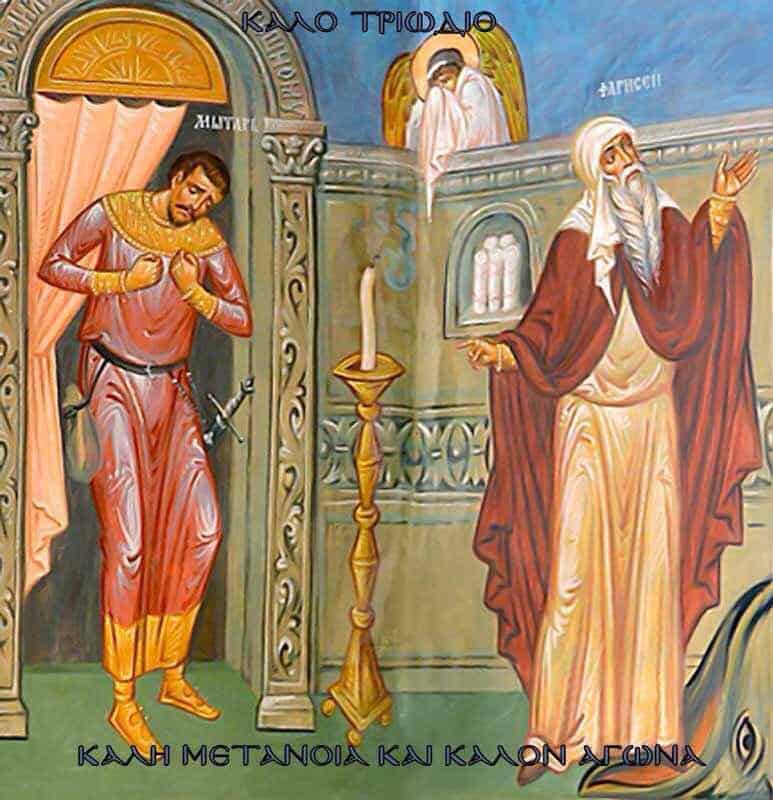

“And the tax collector, standing afar off, would not so much as raise his eyes to heaven, but beat his breast, saying, ‘God, be merciful to me a sinner!’ I tell you, this man went down to his house justified…”

If there was a question answered in this week’s Gospel, it is this: who gets to heaven justified? The punch line, after all, is “this man went down to his house justified.” Again dealing in binaries, as Jesus often does (no grey areas with Him), Jesus sets up the one who went home justified against the backdrop of the one who exalted himself, the Pharisee.

Jesus starts up the parable, of course, dealing with another question: what about these Pharisees who trust in themselves because they are righteous and despise others? But He ends on a positive note, describing not only not how to act, but how to act.

And how should we act? “And the tax collector, standing afar off, would not so much as raise his eyes to heaven, but beat his breast, saying, ‘God, be merciful to me a sinner!’ ”

Let’s parse that.

We begin with how the publican stands afar off. There is a spacial dimension to this week’s parable that cannot be overlooked. Sufis are Islamic Gnostics, and there is a Sufi tale about a man who goes out to seek God, only to traverse miles of terrain and come to a place where he realizes God is in himself. How nice. The God of this parable is not such a God. He comes in a temple, is hidden behind a curtain, and is approached in a certain way, through priests, sacrifices, and properly followed rituals.

And that’s not just some Old Testament way of doing religion that more enlightened times transcend. No, it lays down the foundation for Jesus. If it took some four books of the Torah – the Torah! – to articulate proper worship, as much should we meditate and contemplate on the details and mysteries of the person of Christ, who is the new testament temple and fulfills every detail of the Torah. A theology that glosses over Old Testament details and acts as if they mean nothing now is a theology that also ignores the importance and mysteries of who Christ is, turning Him into a mere archetype, or cosmic messenger, or guru-like teacher. No, we have to get into the nuts and bolts of Jesus, precisely because He’s founded on the Torah’s detailed account of the temple.

And one of those details is the spacial dimension. If He is God in flesh, then He is God in location, outlined and bordered off from other things away from us. To get to God isn’t to go into ourselves because God is everywhere. It’s to go to Jesus.

Jesus is the temple, and He, as that temple described in the parable, is large enough to include the begging and the justifying. Jesus is both beggar and justified. He sighs and cries on our behalf, along with the publican. He is also justified on our behalf, ascending to God’s right hand on our behalf as our righteousness. And He sends the Holy Spirit to share with us both the begging (the Holy Spirit crying “Abba Father” in us) and the justification (the Holy Spirit confessing “Jesus is Lord” in us).

All this happens in the Church, the Holy Spirit’s creation, created where people cry “Lord have mercy” and are justified. What is it to be justified? It’s to be reckoned righteous not on account of one’s own righteousness – that is the righteousness of the Pharisee – but on account of God’s righteousness, that is, His forgiveness, love, and mercy. We’re justified not because we do something, but because God forgives us our sins, causing us to become righteous, justified, before Him.

This too centers on Christ, who ascended to the Father and is our righteousness and sanctification before the Father. This status is administered to us by the Holy Spirit through ministers, in the liturgy. After the Holy Spirit prays in us the publican’s prayer, the Kyrie, the confession, the Lord’s Prayer, we most certainly stand in God’s presence, at His very table, and are reckoned with Christ as His holy, treasured family, His dear children. This is justification.

And there is no purgatory on the way to the altar.

The Pharisee in the parable represents the very doctrine of justification Martin Luther was against in the Reformation. It was taught that we are not justified the way the tax collector was, by first humbling ourselves to the zero point, confessing our sins, and begging for mercy, and then receiving the declaration of Jesus that it was he who went home justified. Rather, it was taught that we are justified after God’s grace works with us to make us good people. What sort of people? The sort of people who do not exhort, commit adultery, or steal, but who fast and tithe.

And what sort of worship arises from both views? The latter view necessarily results in a worship which says something to the effect of, “God, I thank you that you’ve made me so good by your grace. Whatever I am I am by Your grace. Thanks for that!”

The former view results in a different kind of worship. Our involvement in the worship is always supplicatory. We are the beggars needing help. We presume nothing. Meanwhile, we confess God to be everything, our everything, our only source of hope to be anything.

Interesting, but the liturgy – which looks very much like it did in pre-Reformation – has always looked like that second way of worshiping. Unfortunately, the teaching of the Church has not always matched up with what happens liturgically. Liturgically we are the tax collector, begging for mercy and then being justified. No purgatory, just forgiveness and table fellowship, just dying, rising, and joining Christ at the feast. But somehow these doctrines crept in, and a new doctrine of justification crept in that created an incongruity between what happened liturgically and what was believed to happen theologically – you don’t die and go with Christ; you first have to sizzle in purgatory so you can be purified.

Martin Luther embraced what Jesus taught about justification. The beggar went home justified. No wonder Luther’s last words were, “We are beggars, this is true.” Beggars go home justified.