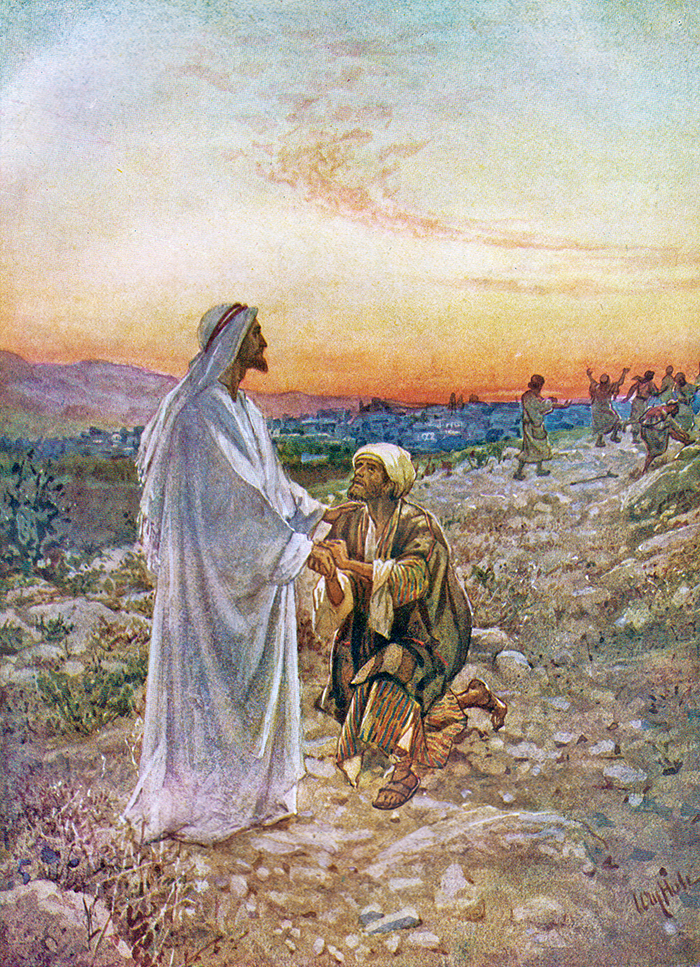

And one of them, when he saw that he was healed, returned, and with a loud voice glorified God, and fell down on his face at His feet, giving Him thanks. And he was a Samaritan.

We can’t ignore the ethnic dimension of both this week’s Gospel and last week’s. It’s simply there and there in a strong way. The Samaritan showed mercy to the wounded man, and a Samaritan returns thanks to Jesus. But I caution reading the wrong thing, usually from a Marxist or Gnostic perspective, into issues of race or ethnicity in the Bible.

What does that mean? Due to Marxism and Gnosticism, funneled to us by Hollywood, there’s a temptation to ascribe numinousness to racial minorities, particularly if they are poorer. Because they’re a minority “other,” so it is believed, they are excluded from the dominant structures of power managed by the racial, religious, or political majority. Excluded from the “system,” they have no loyalty to it, and recognize it as a false construct set in place only to keep power for the majority members. They see things more clearly; they’re more “woke.”

We see this trope constantly in movies. The moral compass of a movie is often represented by an ethnic minority, someone poor, someone crippled in some way, or someone who’s simply “other” relative to the “structures of power,” whatever that means.

Such would be the Samaritans, as evidenced by the good Samaritan, for instance. The priest and Levite were blinded by their system, and so weren’t freed from the constructs created by their interpretation of the Law. But the Samaritan was not so bound, so he was “woke” enough to show the true love.

The Gospel recognizes no numinousness in race, poverty, or minority status. What it does recognize is the expansion of God’s mission to non-Jews. And here, the Samaritans – the first gentiles, you might say – represent something huge in the Gospel. Jesus simply didn’t have a lot of Greeks at hand with which to make His point. Samaritans were the non-Jews available.

In both Luke’s uses of Samaritans, the Samaritan was less bound by the Law, but in both cases, the Samaritan represented someone recognizing a greater fulfillment of the Law. Like the Samaritan woman at the well, to whom Jesus taught a new Trinitarian worship not centered in Jerusalem, the Samaritans in Luke represented a faith not trapped in a bad theology which couldn’t see in Christ the fulfillment of the Law.

The priest and Levite mindlessly abandoned someone out of a misreading of the Law; the nine lepers mindlessly went on to the priest, ignoring the amazing cleansing they just received and what this meant. Not so the Samaritans. It wasn’t because they were granted special powers, being ethnically different, but because they represented the expansion of God’s mission to gentiles.

Interestingly, but there’s a parallel between this week’s Gospel and Jesus’ conversation with the Samaritan woman, as far as gentile worship goes. To the Samaritan woman, Jesus taught that, while in the past worship centered in the Jerusalem according to the Law, the time is coming when people will worship God “in spirit and in truth,” in a Trinitarian way, and that this would bring together peoples away from their particular “mountains.” (Note, also, that Jesus basically tells the woman the Samaritans are wrong about their theology and their particular mountain; “for salvation is of the Jews.”) To worship God in truth is to worship Him in Christ, to whom the Spirit testifies, and whose possessions the Spirit delivers to us.

Now lets look at the Samaritan leper. Like the Samaritan woman, he didn’t have such loyalty to Jerusalem and its laws, so to speak. But if we take Jesus’ conversation with the woman as a guide, Jesus wasn’t necessarily endorsing why the Samaritan leper perhaps had no loyalty to the Law. “Salvation is of the Jews” means nothing if the Law isn’t driving that statement. So, no numinousness!

However, the leper acted out what Jesus was teaching the Samaritan, that is, worshiping God in spirit and in truth. As it says, he “glorified God, and fell down on his face at His feet, giving Him thanks.” He glorified God through Jesus Christ, giving thanks. Thanks is an offering offered by the Spirit. And of course, the healing itself was mediated by the Holy Spirit, the Lord and Giver of life, who was delivering what Jesus would provide once He sat down at God’s right hand, the restoration of the Tree of Life.

And the “truth” is Jesus. He was at Jesus’ feet, recognizing the borders of God in the flesh and blood of Jesus Christ. Truth as far as God is concerned is recognized from non-truth, and in Jesus’ case, non-truth is wherever Jesus is not. Positioning oneself lower than God is an act of humility leading to exaltation, and if the truth is that God is bordered by the flesh and blood of Jesus, there cannot be anything of God-in-Christ higher than me, which means I drive myself as low as I can relative to Jesus, which means being at His feet.

Glorifying God and giving thanks. Those, again, are spiritual offerings, the offerings of the liturgy. You could even say glorifying God is the cornerstone of worship in the first half of the liturgy – Gloria Patri, Gloria in Excelsis, Creed – where giving thanks (Eucharist) is the cornerstone of worship in the second half.

In any event, Luke’s Samaritan here puts some meat on what John’s Samaritan talks to Jesus about, worshiping in spirit and in truth, not bound by Jerusalem. What begins in Kyrie is followed by absolved healing, glorifying God through Christ, confession of Christ as God, and thanksgiving. (If only this could have segued into one of those meals Luke’s so often willing to include!) But this is what worshiping God in spirit and in truth looks like. The Samaritans lead the way for all us gentiles.